Welcome to the Alfred A. Arraj U.S. Courthouse

Welcome to the Alfred A. Arraj U.S. Courthouse

The newest addition to downtown Denver's Federal District. Completed in October 2002, the Alfred A. Arraj U.S. Courthouse is located on a 2.5-acre block in downtown Denver.

It completes the four-block Federal District that includes the U.S. Customs House, Byron G. Rogers Federal Office Building and Courthouse and the Byron White U.S. Courthouse. The site is bounded by 20th Street on the northeast, Curtis Street on the northwest, Champa Street on the southeast, and 19th Street on the southwest. A plaza and public entrance face 19th Street to the southwest not far from the city's central business district, and is adjacent to the existing Federal District to the southeast.

The courthouse occupies less than 35% of the site, leaving ample space for a planned future expansion to the east. Developed to have a 100-year life cycle, it has been awarded the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) silver rating by incorporating the latest 'green' technologies and serves as a model of sustainable and environmentally-conscious design. The Alfred A. Arraj U.S. Courthouse was designed by HOK and Anderson Mason Dale Architects, the general contractor was PCL Construction Services and was built and is owned by the U.S. General Services Administration's (GSA) Public Buildings Service.

The Courthouse houses the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado and the U.S. Marshals Service. The 326,686 gross square footage facility is composed of two parts including a 10-story tower with 14 courtrooms, (10 district courtrooms and 4 magistrate judge courtrooms) and a 2-story pavilion housing the Special Proceedings Courtroom. The courthouse was designed to fulfill expansion needs for the District of Colorado in a secure environment over the next 30 years. Above the three-story base of granite and limestone, the tower is clad in light buff-colored brick, aluminum, and glass. The curtain wall is subdivided by perimeter light shelves. The lower picture windows are tinted to reduce glare and control heat. The upper transoms windows are fabricated with clear glass to maximize the harvesting of sunlight, which is reflected and bounced deep into each floor. At the top of the tower there are 126 photovoltaic panels containing 60 solar cells. The plaza paving is made of Colorado Lyons Red Sandstone and flagstone set in sand beds rather than concrete to absorb water and help control runoff. The plaza contains a xeriscape of hardy regional plants that are low maintenance and drought tolerant. A water feature runs from the sidewalk to the building entrance symbolizing nearby streams of the high desert.

Inside the building, the majority of the interior floor and wall panels are Indiana Limestone, light in color. Ggypsum board walls with heavy texture paint are in the public corridors. Granite floor and wall panels are used in the elevator lobby and elevators. All paints are low in volatile organic compounds and water based. Used throughout the lobby and courtrooms are maple furnishings and wall paneling from the forests in Pennsylvania. The courtrooms consist of cork flooring, which is a renewable natural resource. Acoustical panels surround the courtroom along with honed gray Dakota granite panels behind the judge's bench. The public corridors of the building are oriented to the southeast to maximize solar exposure. Oversized windows provide visitors with a connection to the outdoors and magnificent views of downtown. Internal light shelves bounce daylight onto light-colored surfaces so that it reaches deep into the interior. Fluted glass panels bring diffused daylight into the interior courtrooms and other spaces. Automated shades can provide 50% or 100% opacity when needed. Its southern orientation maximizes exposure to sunlight so that 75% of the interior is naturally illuminated throughout the building. The lighting system takes maximum advantage of the daylighting by incorporating electronic dimming ballasts, occupancy sensors, and low-level ambient lighting. The luminance levels are selected to work in harmony with the natural lighting and high performance glazing systems to provide a balanced luminous environment with low energy consumption. The building automation system is state-of-the-art to optimize building systems within the top 20% of performance. The custom-designed energy management system monitors outside temperatures to optimize heating and cooling loads and neutralize the impact of weather extremes, weekend building closures, and other conditions that can compromise interior comfort. In keeping with tradition, GSA promotes technical innovation and plays a leadership role in providing environmentally sensitive building design, construction, and management practices.

Inside the building, the majority of the interior floor and wall panels are Indiana Limestone, light in color. Ggypsum board walls with heavy texture paint are in the public corridors. Granite floor and wall panels are used in the elevator lobby and elevators. All paints are low in volatile organic compounds and water based. Used throughout the lobby and courtrooms are maple furnishings and wall paneling from the forests in Pennsylvania. The courtrooms consist of cork flooring, which is a renewable natural resource. Acoustical panels surround the courtroom along with honed gray Dakota granite panels behind the judge's bench. The public corridors of the building are oriented to the southeast to maximize solar exposure. Oversized windows provide visitors with a connection to the outdoors and magnificent views of downtown. Internal light shelves bounce daylight onto light-colored surfaces so that it reaches deep into the interior. Fluted glass panels bring diffused daylight into the interior courtrooms and other spaces. Automated shades can provide 50% or 100% opacity when needed. Its southern orientation maximizes exposure to sunlight so that 75% of the interior is naturally illuminated throughout the building. The lighting system takes maximum advantage of the daylighting by incorporating electronic dimming ballasts, occupancy sensors, and low-level ambient lighting. The luminance levels are selected to work in harmony with the natural lighting and high performance glazing systems to provide a balanced luminous environment with low energy consumption. The building automation system is state-of-the-art to optimize building systems within the top 20% of performance. The custom-designed energy management system monitors outside temperatures to optimize heating and cooling loads and neutralize the impact of weather extremes, weekend building closures, and other conditions that can compromise interior comfort. In keeping with tradition, GSA promotes technical innovation and plays a leadership role in providing environmentally sensitive building design, construction, and management practices.

The Alfred A. Arraj U.S. Courthouse is an example of GSA's continuing commitment to Design Excellence and being stewards of the environment in creating outstanding facilities to serve the American public.

How the Sundial Works

Sundials, like the one on the Alfred A. Arraj U.S. Courthouse, measures the apparent solar time at the specific location where the dial is placed.

Sundials, like the one on the Alfred A. Arraj U.S. Courthouse, measures the apparent solar time at the specific location where the dial is placed.

The protruding gnomon casts a shadow which tracks the hours as the day progresses from sunrise to afternoon. The length of the shadow varies depending on the time of year. Lines indicate where the shadow reaches on the Summer and Winter Solstice and the Vernal and Autumnal Equinox.

There are many types of sundials: declining, inclining, reclining and equatorial dials. The Arraj Courthouse displays a declining dial. Because of the location of the wall, the dial 'declines' 48.08 degrees east of south in a vertical position. The length of a day is not constant throughout the year because of the lack of geometric perfection in the spherical shape and elliptical path of the earth. Since the 24 hour day is a mathematical average (or mean), discrepancies occur between the apparent solar time (the sundial time), and the time shown on your watch. Adding and subtracting minutes from reading the sundial according to the month of the year is required. A further adjustment is also required during daylight savings.

Art In Architecture - Exterior Wall Art

Art has always been an important feature of great architecture. One installation has been created specifically for the Alfred A. Arraj U.S. Courthouse.

Art has always been an important feature of great architecture. One installation has been created specifically for the Alfred A. Arraj U.S. Courthouse.

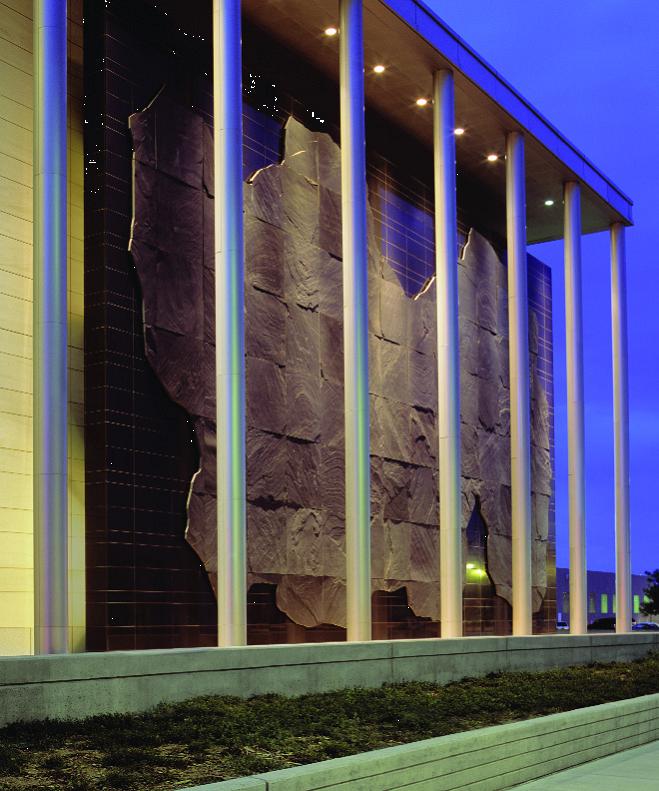

The piece is located on the exterior of the building, along the Champa Street side of the courthouse. Irregular Form Gray Slate Mortared to a Black Granite Supporting Wall 36 Feet by 70 Feet Side Wall of the Entry Pavilion Sol LeWitt Irregular Form is an expansive "wall drawing," a term that connotes both the artwork's flat, linear nature and artist Sol LeWitt's use of the wall itself as an art material. Comprised of irregular slabs of gray slate on a black granite background, the artwork's immense scale and striking contour exert a commanding presence in its urban environment. Captured within a sturdy, grid-like framework that references the rational, geometric ordering of the entire building, the unwieldy appendages of the gray form are firmly anchored to the supporting architecture. This playful tension between organic and geometric elements is a hallmark of LeWitt's innovative wall drawing technique.

LeWitt considers the architecture an integral component of his work, using the walls as parts of the compositions and for drawing. Although the irregular gray form projects from the wall in low relief, like an extra layer of skin, it was not conceived as a decorative sculpture affixed to an inert wall surface. Instead, Irregular Form is a part of the architectural fabric of the courthouse. The interplay of the artwork's gray and black areas allows each to be read alternately as positive figure and negative void. In this artwork, LeWitt eliminated all representational subject matter in order to focus attention on the formal grammars of line, shape, texture, color, and scale. The temptation, however, may remain for viewers to discern in Irregular Form some sort of pictorial references-be they geological, botanical, meteorological, or cartographic.